By looking at sûjôdan

As remarkable as it is that Sekisui, born into a common household, managed to become a servant of the Mito domain at the age of 52 due his successful studies, he still was living in a village in the countryside until he turned 61. Because of that it is only natural that he was very familiar with the actual situation farmers lived in.

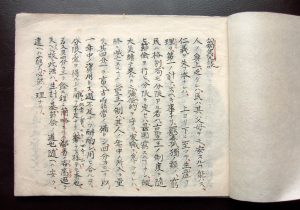

He probably was asked for his opinion on agricultural policy by local country magistrates. In his 57th October Sekisui revealed his work “sûjôdan”. Sûjô refers to the cutting of grass and trees and is a most humble way for a peasant to refer to oneself.

In the beginning it says: “If the common man is poor, he isn’t able to provide for his parents. Because this poverty leads to the loss of all moral it is of utmost importance that everybody, independent of status, learns how to manage spending and production”

sûjôdan (collection by Kazuyoshi NAGAKUBO 25.3 ✕ 17.7cm)

sûjôdan (collection by Kazuyoshi NAGAKUBO 25.3 ✕ 17.7cm)

Further it says that one will have nothing to worry about if one lives a humble life, knows his place and follows the ancient system implemented by Prince Shôtoku.

This system suggests to save one fourth of a year’s harvest to prepare for trying times and live from the other three fourths.

In the last part he writes that a wise ruler should rethink unnecessary expenditures he feels bound to by old social rules and rather should balance his accounts.

By looking at “nômin shikku” (The peasant’s suffering)

Penalties during Sekisui’s time were harsh. In his text “hyakushô nichiyôkun“(Every day words of peasants) Genjun Suzuki mentions “direct appeal, complain, forming cliques, joint signatures, armed rebellion… in serious cases punishment by death in prison, in not so heavy cases imprisonment, exile, cutting off ears or noses”

Without even looking deeper into a complaint, bans were given out with no arguments being allowed.

Even when Sekisui became a jikô and therefor belonged to the ruling class, in heart he still was close to farmers and peasants.

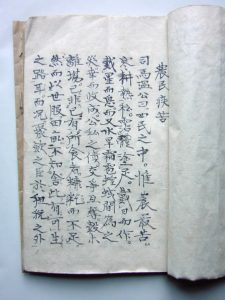

And those cried in the shadows about their treatment and taxes. A few pounds more rice here, a further few pounds there. To make it even worse, after they worked hard loading the ships and driving up the Nakagawa, after arriving in the Mito domain, they once more had to open their rice sacks for inspection. This was the so called “saiaratame”.

nômin shikku (The peasant’s suffering) (collection by Hashimu NAGAKUBO 16.5 ✕ 24.6cm)

nômin shikku (The peasant’s suffering) (collection by Hashimu NAGAKUBO 16.5 ✕ 24.6cm)

If the officials in charge had a bad day, the rice was thrown into a grain fan and then the peasants were sent back to their villages being accused of short delivery.

In his first year as jikô, after earning status and reputation, prepared to die Sekisui delivered his text “nômin shikku” to the lord of the Mito domain.

“Even if shining light on the unnecessary cruel treatment of the unfortunate common folk means that this servant [Sekisui himself] risks his head to be cut off his shoulders, he is prepared for this”.

“Moved to tears and deeply ashamed I write to you this inexcusable letter”

Thanks to his writing saiaratame was abolished.

The abolition of the Ôno farm

Sekisui realized reforms of child care, saiaratame, and many others. One of those is the so called “nogoma no nan aiyami sôrô”.

This refers to an accident occurring at the Ôno farm at Matsuoka in the Mito domain (today’s Takahagi). It all started with Mitsukuni Mito releasing 13 horses into the valley of Ôno village in 1678 and later setting 62 additional horses free. The region was named ôno tabata nogomayama and became a place famous for raising excellent horses. The problem though was, that the loose horses started to eat the harvest from the surrounding fields, which posed a big problem to the local farmers. This was in a time, when the word of the lord was the rule of the land and Mitsukuni held a status comparable to a god. How could one stand up for his rights in such a situation? The horses destroyed the crop and harvest and the damage got worse year by year. So with no other choice left, a plan for a self-defense was forged. “A call went out and from 35 or so villages around 2800 laborers were gathered to build an earth embankment with a height and width of three meters each”. (Tsuneo Yamaki: Ashita no kaze to hitotsu ni natte).

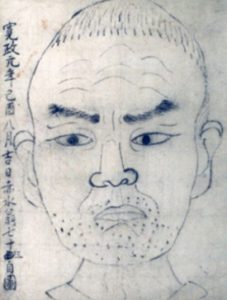

Sekisuiga (Selfportrait by Sekisui NAGAKUBO) (collection by Tomoyasu NAGAKUBO 19.1 ✕ 25.2cm)

Sekisuiga (Selfportrait by Sekisui NAGAKUBO) (collection by Tomoyasu NAGAKUBO 19.1 ✕ 25.2cm)

“In times of peace there is no need for war horses. The system should change according to the changing times”, Sekisui pled to his superiors to help the troubled farmers. Other important servants also expressed their discontent with the farm created by (by then already deceased) Mitsukuni. And so, maybe for the celebration of Sekisuis 70th birthday eight years later, the Ôno farm was abolished.